Towards a Just Peace

A year ago, Palestinian Christians issued a historic call for global solidarity – and got a timid response from those fearful of being branded antisemitic. Ben White believes genuine interfaith dialogue is only strengthened when we speak out boldly on injustice.

Living on the family farm outside Bethlehem, Daoud Nassar is under constant threat from the illegal Israeli settlements that have sprung up around him. When I visited last summer, he had just had a new crop of demolition orders delivered by Israeli soldiers, targeting ’structures’ ranging from animal sheds to water cisterns and tents.

‘Of course, we will never get a building permit here,’ he told me sadly, as his little boy sat eating crisps on his lap. ‘But I said to the Israeli officer, if I need a permit just for my tents, I’m also expecting you to go to my neighbours and give them demolition orders for their buildings, built on Palestinian land. And of course, his answer was, ‘This is none of your business.’1

Daoud’s is a story shared by most Palestinians living under Israeli military rule. They are not looking for special favours: just the same basic rights afforded to others – and an end to the impunity enjoyed by Israel as it continues to maintain the West Bank as an archipelago of apartheid and privilege. But to achieve even this basic freedom, they are going to need our help.

A CRY OF HOPE

One year ago in December, from their community’s lived reality of suffering and struggle, Christians in Palestine issued an historic cry for solidarity and justice, with the launch of the Kairos document.2 Written by clergy and theologians, Kairos Palestine was the work of over a dozen community leaders, and deliberately echoed the South African Kairos declaration published 25 years ago. Announcing a ‘moment of truth’, the document addresses fellow Palestinians, Israelis, and crucially, ‘Christian brothers and sisters in the Churches around the world’. It is a cry of hope, but also a cry for solidarity and response.

The document speaks clearly about the reality for Palestinians under Israeli military rule, an occupation described as ‘a sin against God and humanity because it deprives the Palestinians of their basic human rights, bestowed by God’, as well as distorting ‘the image of God in the Israeli who has become an occupier’. To Christians in the West, the Kairos document is uncompromising in its criticism of those who ‘attach a biblical and theological legitimacy to the infringement of our rights’. Celebrating the Church’s mission to stand alongside the oppressed, Kairos Palestine asks us a pointed question: ‘Are you able to help us get our freedom back, for this is the only way you can help the two peoples attain justice, peace, security and love?’

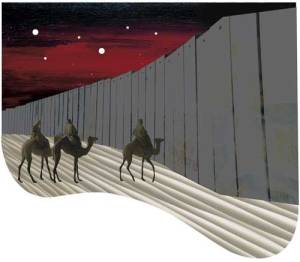

Despite the fact that Kairos Palestine was carefully-crafted contextual theology from a threatened minority, speaking to the heart of one the most contentious conflicts in the world, the response from the Palestinians’ Christian brothers and sisters has been mixed. There have been strong, positive responses in the likes of Sweden, Norway, Malaysia, Canada and South Africa, where a particularly strong statement labelled the practicalities of the Palestinian situation as ‘even worse than South African apartheid’.3 The Presbyterian Church (USA) commended Kairos Palestine to its members at this year’s General Assembly, as did Britain’s Methodists. The latter voted for a boycott of products from illegal Israeli settlements, a step also taken by the National Council of Churches in Australia this summer.4 At this year’s Greenbelt festival, the ‘Just Peace’ campaign continued, with a mock Separation Wall on site, as well as a range of talks on justice issues, Jerusalem, and boycott.

DISAPPOINTING SILENCE

Yet there has also been a disappointing silence from some quarters, or at best, a cautious welcome that deliberately stops short of endorsement and practical response. A good example of this timidity was the document submitted to the Church of England’s General Synod in May, by the Mission and Public Affairs Council.5 While there were plenty of affirming noises, the end result of MPAC’s response was to commit the Church of England to precisely nothing: Kairos Palestine deserved a ‘wider readership’, but merely as a ‘valuable resource’ if read alongside other sources. Not for the first time in the Church’s history, the uncomfortable voice of the colonised is quickly qualified, cushioned, and neutralised.

The tepid response from some to Kairos Palestine is unfortunately symptomatic of a more general weakness. For years, church leaders and bishops have kept their pronouncements restricted to anguished cries for an end to bloodshed on ‘both sides’. While many churchgoers in Britain have increasingly understood the need to take action for basic Palestinian rights as a prerequisite for a just peace for all the people of the land, leaderships and institutions remain hamstrung by fear of the backlash and a concern to preserve high-level interfaith relations with the Jewish community.

A good example of these issues made headlines earlier this year, when British Methodists passed a Palestine/Israel report at their annual conference that had been prepared by an internal working committee during the previous year.6 Their overwhelming adoption of ‘Justice for Palestine and Israel’ was historic not because it expressed support for Palestinian rights, but rather because it proposed and endorsed concrete steps in order to realise these rights – including a boycott of products from Israeli settlements. These are not just illegal under international law: they are the infrastructure of apartheid. On a visit to the Jordan Valley this year, I picked my way through the broken remains of Palestinian homes and shelters, demolished by the Israeli military, while all around, Israeli settlements produce fresh produce for European markets.7

ZIONIST LOBBYING

In the build up to the conference, Methodist leaders came under intense pressure from several Jewish community leaders, as well as Zionist pressure groups, to reject the report. Yet when delegates gathered, they had also received voices of support from Christian Palestinians and Jews (both in Israel and the UK). Many of those signed a statement which affirmed that:

We do nothing to advance a just peace without being realistic about the structural imbalance between Israel and the dispossessed, stateless Palestinians. In 1963, Martin Luther King wrote that the greatest ’stumbling block’ to freedom was the ‘moderate’ who preferred ‘a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice’.8

An interesting lesson from the Methodist conference’s Palestine/Israel report, and particularly the angry opposition it provoked, is that when Christian groups stand their ground, the response by Jewish groups and Israel advocates is to call for further dialogue, not less. In the two weeks leading up to the UK Methodist conference in June, there were warnings by the likes of the head of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks that, if passed, the Palestine/Israel report would ‘damage interfaith relations’.9 Yet once conference had overwhelmingly adopted the working group’s report and resolutions, the response by groups like the Council of Christians and Jews (CCJ) was to encourage members to deepen the conversation with their local Methodists. Indeed, British synagogue leaders were reported as having subsequently set up a ‘task force’ of scholars and rabbis to ‘put its point of view across at a meeting with Methodist representatives’.10

FEAR OF ANTISEMITISM

There was a similar irony in the response ‘before and after’ when it came to the Presbyterian Church (USA)’s Palestine/Israel report this summer. During intense discussions, aspects of the draft text were altered, yet the substance – and its clear solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for basic rights – remained unchanged. Whereas prior to the General Assembly, the Wiesenthal Centre had condemned the report as ‘poisonous’ and a ‘declaration of war on Israel’, afterwards, an umbrella Jewish group who had organised against the report praised the ‘more thoughtful approach to Middle East peacemaking’ and pledged to ‘remain partners’ in the search for understanding.11

Long-standing assumptions about the limits of Jewish-Christian dialogue are beginning to crumble as we acknowledge the elephant in the room. Professor Marc Ellis has written much about the ‘ecumenical deal’ that emerged from post-Holocaust Christianity, whereby (still) necessary work on antisemitic theology became, in part, a way for Israel to be an ‘exception to criticism on human rights violations’.12 This lack of accountability is only reinforced when criticism from the Church is branded as a form of anti-Semitism. As Jerry Haber, an orthodox Jewish philosophy professor, pointed out on his website in August: ‘When Jews, and I mean here liberal Jews, are open to religious dialogue with Christians and Muslims, they have no difficulty in respecting difference. But when it comes to Israel, they demand that the other side accept the Zionist narrative, or, at the very least, be open to accepting it.13

THREE STEPS

There are differences between the dynamic in the US and the UK, particularly at the grassroots level. But at the level of senior church and institutional leadership, interfaith ‘considerations’ mean that the voice of the occupied is barely tolerated when it comes to Palestine, let alone granted the response it demands. As author and peace activist Mark Braverman put it, a key consequence of ‘the charge of anti-Semitism and the prospect of a disruption in the ‘interfaith partnership’ has been the thwarting of actions directed at Israel’s policies.14 David Gifford, chief executive of CCJ in the UK, attacked the Methodist’s report for apparently offering no real solutions and throwing everyone into ‘even greater desperation’. By contrast, Kairos Palestine called its appeal for solidarity a ‘cry of hope’ – an emphasis shared by US Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb, who described the Boycott Divestment Sanctions as a ’sign of hope’ fully in keeping with her commitment to ‘the Torah of nonviolence’.15

I would like to propose, therefore, three ‘keys’ for the Church’s engagement with Palestine/Israel – three steps towards a just peace. These are intended to be shaped by the contours of the Kairos document itself.

RECOGNISE REALITY

The first key is for our response to be shaped by the reality on the ground. On eight trips since 2003, I have witnessed how Israel’s policies towards the Palestinians are shaped by the priorities of colonialism: maximum land with minimum Palestinians, and maximum number of Palestinians on the smallest amount of land. Nor is it just the demolitions of homes, the confiscation of land, and the Separation Wall of the West Bank. There is Gaza: besieged and battered, a prison for 1.5 million people. Furthermore, Palestinian citizens of Israel (a minority of 20%) are also targeted. I have been to ‘unrecognised’ communities in Israel ‘proper’, where the state’s own citizens live with home demolitions and harassment, while adjacent Jewish neighbourhoods and towns expand.16

This miserable diary of dispossession and displacement only skims the surface of what are routine occurrences in Palestine/Israel: they take place day in and day out, week after week, away from the TV crews (and pilgrims). This is the Palestinian reality: your brother snatched in the night by masked soldiers; beatings and gunfire at non-violent demonstrations against the Wall; checkpoints controlling your movement; your olive trees hacked down by settlers. Yet Israelis, in the words of Ha’aretz columnist Gideon Levy, ‘aren’t paying any price for the injustice of occupation’.17 Recognising this imbalance isn’t about dehumanisation: as Martin Luther King understood in his own context, given that the structure of segregation had corrupted white American society, the struggle for equality meant (different kinds of) emancipation for both sides of the power divide.

SHALOM SPEAKS OUT

The second step is to grasp that, in the words of a member of the Council of Christians and Jews, interfaith dialogue is not well served ‘by being coy about what we believe to be true.’ Real dialogue is not that of fear or ‘deals’, and Jews do not speak with one voice on Palestine/Israel. To stand in solidarity with the Palestinians, to seek to act and resist occupation and domination, is to heed the call of countless Jewish dissidents and activists, on the ground and in the West.

The third step is to embrace the implications of the fact that it is justice that ‘will produce lasting peace and security’ (Isaiah 32:17). One of the reasons for this is that, short of the annihilation of one side, peace without justice is unsustainable. But a second, deeper reason can be found in the full meaning of the Hebrew word shalom. Shalom is not merely the negative peace of a lack of war but ’something much richer’ – it is not the absence of violence but rather, the presence of justice.18 In Palestine/Israel, it means a vision of that land shaped by the prophet Micah, where everyone ‘will sit under his own vine and under his own fig tree, and no one will make them afraid’ (Micah 4:4).

THROUGH THE WALL

Nabil Saba’s father tended his own, treasured fig trees and vines until the Israeli occupation forces expelled the family from their land in the 1970s. Now Nabil lives down the hill in Beit Jala, and from his terrace he has had a clear view of the Separation Wall closing in the boundaries of the Bethlehem prison. Nabil once told me that his father, before he died, ’said he wished he could sleep just one more night in his house’.

While it is too late for many, today there are millions of Palestinians crying out for justice, appealing to those of us in the outside world for an end to decades of land confiscation, expulsions, and military rule. Daoud Nassar and his family, like the voice of the Kairos Palestine call, continue to live with steadfast hope – yet without outside intervention, they cannot expect to withstand the bulldozers and bullets alone.

At Christmas, we can expect the usual seasonal coverage of Bethlehem, whether a look at life under occupation or a quick TV spot from Manger Square. But it is not sufficient to be connected to events on the ground just once a year. One way of responding in your local church or community group is to join ‘A Just Peace for Palestine’, a new initiative of Amos Trust which I am helping to coordinate.19 It is a time to mobilise, and speak clearly. It is time for the Church to take action, so that our response to the Kairos call is heard over the Wall and then goes on to break through it.

First published in Third Way Magazine.